Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam of 2023: Masterstroke of Misogyny or Political Empowerment of Women

Rushda Siddiqui

Research Scholar19th September 2023 was a historic moment for democracy and the women of the country when the opposition and the ruling party came together. A women’s reservation bill was being tabled and passed with never seen before unanimity. On 20 September 2023, Lok Sabha passed the bill with 454 votes in favour and two against, on 21 September 2023 Rajya Sabha passed the bill with 214 votes in favour and none against, and finally on 29 September the President of India signed it to make it an Act. On paper, a long standing wish of women’s movements has been granted by a magnanimous government. To prove the point of magnanimity, the bill was named: Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam, or an Act that worships the power of women.

There were some demands put forward by the opposition, but except for two parliamentarians, everyone supported the idea and voted for it. The very reasons for which the bill had not been tabled since 2010, were overlooked by the very parties who had made the objections. Issues of reservation within reservation, OBC reservations, the idea of parties adopting the concept within their own structures, disinterested women and many more reasons were set aside. Interestingly, the BJP itself had opposed the bill as it did not specify quotas for OBCs and Muslim women.

To be fair to the opposition, they did not want to be seen on the wrong side of history. The passing of the bill, like a range of bills against which there has been opposition from the people, could have been done without an opposition, as the ruling party has an overwhelming majority in both houses.

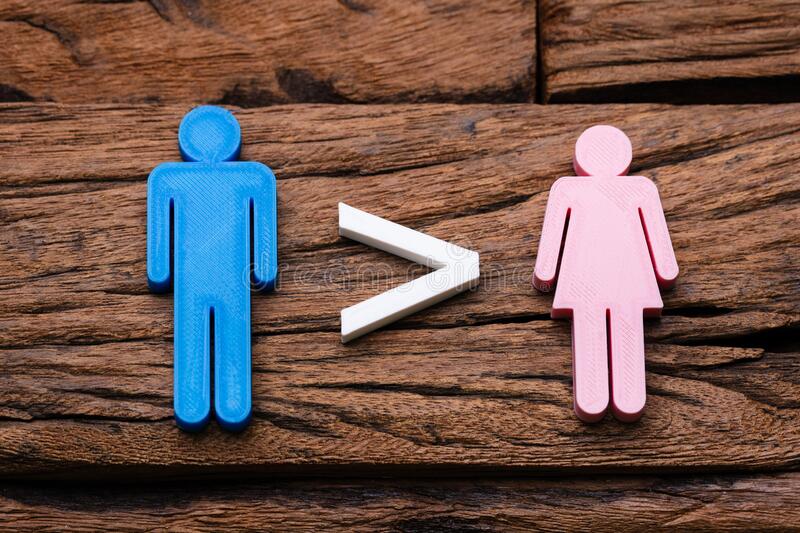

This bill is different as it targets the largest vote bank of the country. Electoral history of India is fraught with promises to women voters and targeting families. Women have always been viewed as subjects of social welfare and not equals. Objections to the concept of women participating in politics have ranged from it will not empower them as their husbands will use them as proxies to only upper class women will benefit from the reservation as urban women are more attractive (Mulayam Singh, 2012). The argument from Nagaland was an exact opposite. Politicians from there emphasised that since the women in the North-East are more educated, they are disinterested in the quagmire of politics.

That women have been seeking their place under the political sun was evident from the 1990s. CPI was proposing the demand in its national congress in 1991. A pioneer in union movements, CPI and other left parties were inundated with requests for demanding reservation for women in elected offices. In 1992, the 73rd and 74th Amendments of the Constitution reserved a third of the seats in Panchayats and Urban Municipal Councils, for women. Civil society and trade unions stepped in to help women contest and understand the reins of governance. Despite the hostility from political parties and social leaders, women were able to make a difference. Bihar was the first state to increase the percentage of elected women at Panchayat and Municipal levels to 50% in 2006. The fight of the women’s movement changed perspectives from women being a welfare subject to being partners in development. As the UN perspectives changed from Development to Empowerment in 1995, the Government of India supported the shift by giving the example of the 73rd and 74th Amendments.

It was this change that boosted women like Geeta Mukherjee and Pramila Dandvate to demand reservations for women in the Parliament and State Assemblies. In 1996 both introduced a bill for constitutional amendment, pointing to the fact that nearly all political parties had been putting the agenda in their election manifestos since the late 1980s. Bills seeking reservation for women were introduced in the Lok Sabha in 1996, 1998, 1999, and 2008. The first three Bills lapsed with dissolution of their respective Lok Sabhas. The Bill introduced in 2008 was examined by the Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice, under the Chairmanship of Geeta Mukherjee. With recommendations regarding rotation of seats, reservations for OBCs and extension of the reservation after 15 years, the Bill was tabled in the Rajya Sabha in 2010, where it was passed as the 108th Amendment Bill.

Passed in the Rajya Sabha, the Bill was defeated in the Lok Sabha. MPs from different political parties gave various reasons, from BJP women MPs voicing concern that political reservation of women will destroy families, to SP members warning of catcalling in the parliament if so many women came to the parliament. The debates ranged from ‘balkati’ women cornering seats by depriving women from marginalised backgrounds to women being proxies and being politically unaware. What was interesting was the fact that most of these arguments came from women parliamentarians, and the parties opposing representation in parliament were supporting increasing the reservation at panchayat and municipal levels.

The success of the 73rd-74th Amendments had led to a surge in women political leadership roles, particularly at the grass root levels. The Joint Parliamentary Committee and the Standing Committee had received letters written in blood, seeking reservation and an opportunity to be part of the policy making process. However, all the voices of women went unheeded. There were demands distracting from the bill, like letting political parties allot a third of its leadership seats to women, so that these women could rise and contest as equals. Or that instead of political reservations, there should be reservations for women in education, particularly at the primary level. Political parties that had a clear majority and could have supported the move, faltered as it would create dissent within their own ranks.

It was a long battle for women’s groups and human rights activists to demand the tabling of the 108th Amendment in every session of the Lok Sabha. The National Federation of Indian Women (NFIW), of which Geeta Mukherjee was a former Vice President, sought the Supreme Court's intervention in 2021 to reintroduce the Women's Reservation Bill passed in 2010. The court sought answers from the government, and wanted to know why the legislation was not being tabled. The Centre’s reluctance to take a clear position on the matter prompted more questions. In 2023, expressing concern over the lack of clarity from any political party on this issue, the Supreme Court postponed the case until October, with clear instructions for the Centre to file its response.

Women's Reservation Bill 2023 is the One Hundred Twenty-Eighth Amendment, 2023. The Adhiniyam too needs to be understood as a gracious act of charity to women, as well as a move to not answer the SC. On the face of it a long-standing demand for political empowerment is being granted, but as a charity that will be disbursed after census, delimitation, political parties are able to rile up candidates and other favourable conditions permitting. So, an Act that will not be implemented in the foreseeable future has been passed.

The debate after voting, has been dominated by the strings of census and electoral delimitation for implementation. In other words, as representation to Lok Sabha is based on population, a more densely populated part of the country will have more representation than the sparsely populated one.

The entire concept of 33% reservation for women in the Act drastically cuts down on the previous bill’s idea of empowerment. The 2010 Bill sought one third of Lok Sabha seats in each state to be reserved, while the Adhiniyam caps the number at 33% in total. The shelf life of the Adhiniyam allows for the affirmative action to be limited to 15 years, while the previous Bill allowed for rotation and reallocation after every general election.

Unequal population spreads make for a skewed representation in the current parliament, where the ‘Hindi heartland’, with its teeming population is able to decide the political ideology of policy making. Though geographically a smaller area, seats from UP, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat can decide who forms the next government. In other words, five to six states out of twenty eight states, can decide the fate of the country. With every delimitation exercise, states with lesser population will lose seats, while the overpopulated ones will gain. A notable feature about states with dense populations is the skewed sex ratio, which some analysts believe is the reason for rampant rise in crime against women. It is also the region that has witnessed a sharp surge of majoritarian authoritarian violence over the last decade. Economically, the densely populated states contribute less to the economy and consume more. The resultant fear of becoming a voiceless colony to the few is bound to spiral into a political whirlpool. The agitation and political unrest has already begun. The process of rotation of seats after each delimitation will be the next contentious issue. If the Bill is implemented in the coming elections of 2024, we are looking at the total number of seats 543 (2 of Anglo Indians will not be counted) out of which 179 seats are to be reserved; within which we are counting 131 (84 SC & 47 ST) being again limited to 33% of 84= 27; 33% of 47 = 15 (so 42 seats in total); 179-42=137 out of which the OBC, minorities and other quotas are being demanded. Once the process of delimitation begins, the calculations will need to be redone.

It needs to be remembered that the Bill that was passed in the Rajya Sabha in 2010 was a bill that was drafted by women. All reservations in the country have only the criteria of identity attached, be it SC/ST, OBC or EWS. Here the entire burden of proving population, eligibility to new seats after each delimitation, all within a span of 15 years from the time of its implementation, makes it the most challenging bill to implement. The Law Minister and Finance Minister, while introducing the Bill in the Parliament were right in talking about the many schemes for welfare and programmes that the government had launched for the good of women in the country, like Beti Bachao Beti Padhao and Ujjwala Yojan. In line with these schemes and legislations, the Adhiniyam was tabled. The Law Minister talked of taking the representation of women from the current 82 to 181, ignoring the fact that the number of seats and constituencies will change significantly after both the census and delimitation exercises. The decadal census has not taken place, and the last Delimitation Commission took over five years to present its final report.

The last point that needs to be kept in mind while discussing the Women’s Reservation Act of 2023, is the manner in which it is leaving scope for hurdles to rise before it can be implemented. There is ambiguity in the reservation for OBCs, minorities and other backward classes. As the caste census details emerge, the demand to restructure the formula for reservations will also get stronger. Also, the act has not taken a stand on reservations in the upper house, either in the centre or the states. It has also not taken a stand on the states that fall into the category of Union Territories (except Delhi), and states that have one or two representatives. A long standing demand for social and political representation in a democracy has been converted into an ambiguous Act to be implemented in some future, leaving everyone confused about intentions and realities.

The author is a social science researcher who is also associated with different human rights movements. A PhD from the School of International Studies, JNU, she works on socio-political dynamics of change.